Radiation therapy and me

They told me three things, over and over:

1. You won’t feel anything at all.

2. The treatment is over very quickly — the actual radiation part just takes a few minutes.

3. The machine will never touch you.

They said that so often (the radiation oncologist, the radiation therapy nurse, the RT techs, the books and websites I consulted), that I realized that these were the three things that most people found most scary. Will it hurt? How soon can I get out of here? What is that thing, and what is it going to do to me?

Those reassurances got said a lot because they usually need to be said a lot.

To the average person off the street, radiation mostly means atomic bombs, and possibly nuclear power stations melting down and poisoning everything, and people dying in horrible, agonizing ways.

The healthcare providers had to work against those preconceptions. They explained, reassured, and tried to make everything as non-threatening as possible.

And I figured, even as geeky as I am, I probably had a lot of those same preconceptions and negative associations stuck way down deep in my psyche, absorbed from the general culture, where they might leap out at me unexpectedly — and, say, cause me to completely freak out during treatment.

Which I did not want to have happen. I’d be getting radiation therapy five days a week for eight weeks, and it would be great if my lizard-brain wasn’t trying to kick me into flee-in-terror mode every time.

Forewarned is forearmed, so I reviewed all the info I was given, read up on the events that would take place during treatment, did a little deep breathing, and reminded myself that all this was happening because things were going better than expected.

According to my original treatment plan, I was going to have two kinds of chemotherapy, a mastectomy, and then some more, lighter chemo (Herceptin only) — and the timing even would even allow me to get to the World Science Fiction Convention in London in August.

But (as my regular blog readers will recall) the two rounds of heavy-duty chemo worked brilliantly. My tumor shrank and shrank, and eventually became undetectable by x-ray and ultrasound. In fact, a biopsy (remember that unplanned biopsy?) actually showed no sign whatsoever of any cancer remaining in the area.

So, no mastectomy after all, gladly. Just a “lumpectomy” (more accurately called a partial mastectomy). A fairly large one, but nothing like a full mastectomy.

But with a lumpectomy, you get radiation. This, to chase down any random cancer cells that might have stayed behind after the surgery, and zap them dead before they do their out-of-control reproduction trick. I knew that there would be side effects to the radiation, and the effects would accumulate (and might become pretty nasty), but the delivery of the radiation doses would not actually hurt, or even be felt at all.

So, I went through all the preliminaries: the CAT scan to identify the exact measurements of the treatment area (so they don’t irradiate more of your body than needs it); the simulation, where they test out the aiming; the tattooing of tiny dots to help with the precise aiming; getting my body position exactly right, and making the custom brace to hold me in that one right position, so that everything is the same each time, no variation — all that.

Eventually we got down to the real deal, and I found myself being led down the little corridor with the large sign saying PATIENTS ONLY IN THIS AREA; and the other sign with the light, saying RADIATION IN USE WHEN LIT; when I noticed another, little sign on the wall by the entrance, reading:

LINEAR ACCELERATOR

Wait, what? I said to myself as we passed it by and continued down the hall.

In the treatment room, the radiation techs ran over everything one last time, including reminding me: I wouldn’t feel a thing; the actual radiation part would be over quickly; and the machine itself would never touch me.

Them: So, that’s about it. Now, before we start, do you have any questi —

Me: Yes. Yes, I do.

Them: Oh — Okay, what’s your ques —

Me: Is this really a linear accelerator?

Them: Well… yes. Yes, it is.

Me: THAT IS SO COOL!

Them: (pause) …what?

Me: Seriously? A linear accelerator? So, subatomic particles are going to be sped up to, like, 99 percent of the speed of light? Right here?

Them: … yes…

Me: For me? Â To zap my cancer? An actual linear accelerator?

Them: Well, yes —

Me: THAT IS SO COOL!

Them: (big pause) … really?

Me: Yes.

Them: Well… you know what else is cool? This whole thing is computer driven, with all your measurements stored, along with the treatment plan and digital control of the specific gantry movements … and we work it from this console over here… there’s a digital 3D mockup of your treatment area, and — would you like to see?

Me: YES, PLEASE.

So they brought me over to the console and showed me the mockup of my treatment area: an exact and precise little bit o’ me, color-coded, rotatable in three dimensions on the screen, and it was also so extremely cool.

Me: This is one slick machine.

Them: It’s amazing.

And it was.

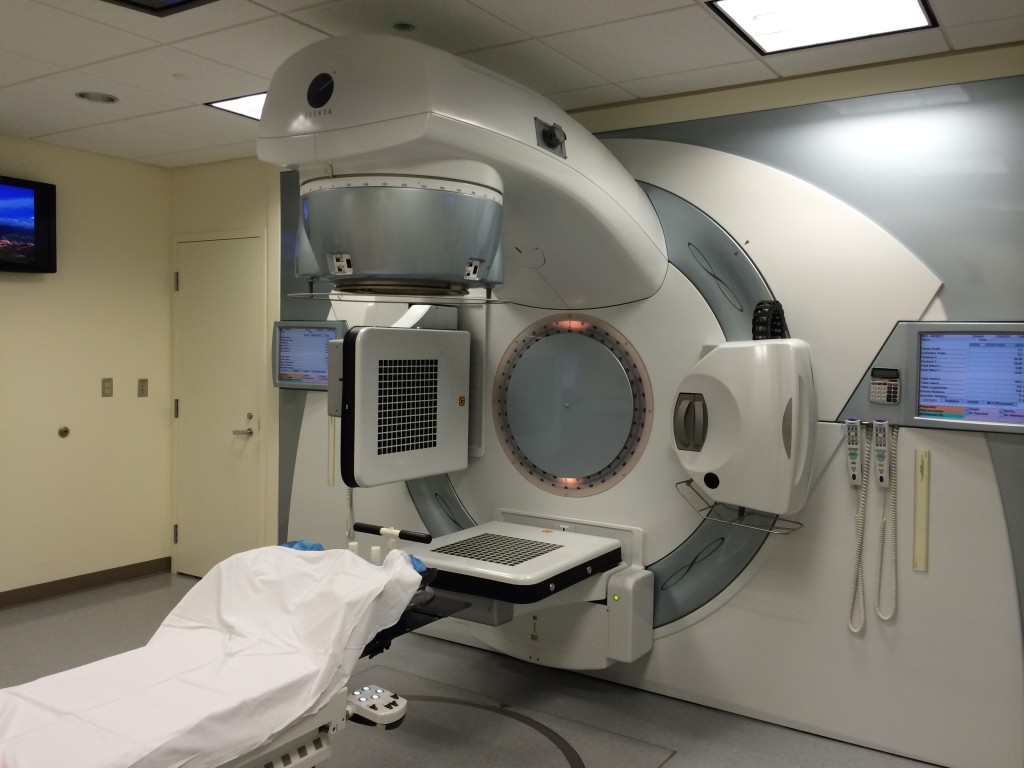

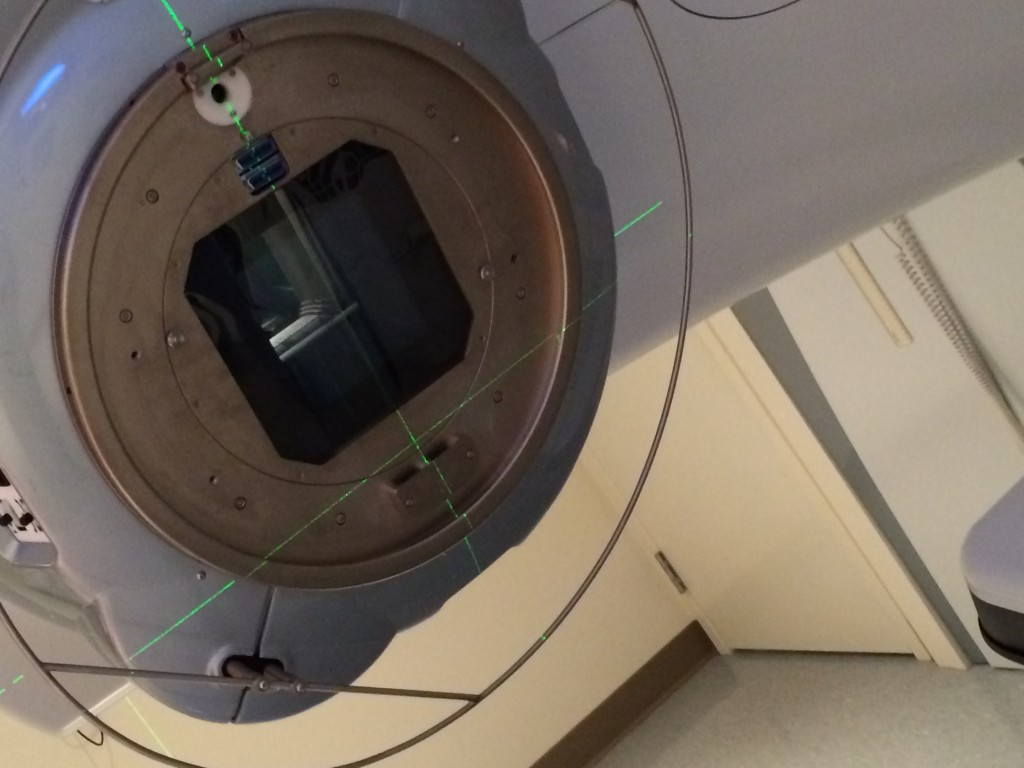

Come on — what sci-fi nerd wouldn’t love this? With all the calibration circles, and the sleek cowling, and the way the gantry completely rotates all around the patient, so once you’re in place you don’t have to reposition at all. Minimal fuss. It’s not just pretty — it’s such a smart design.

Possibly sometime before this point, it had been mentioned to me that a linear accelerator was used, and I just missed it. But, I don’t think so.

I had been told what to do during treatment, and the fact that a machine would be used to deliver the radiation. But somehow I got the idea that they had some, I don’t know, radioactive substance in a container, and they’d point it at me and open a little window of some sort, allowing the radiation to escape and wash across my cells.

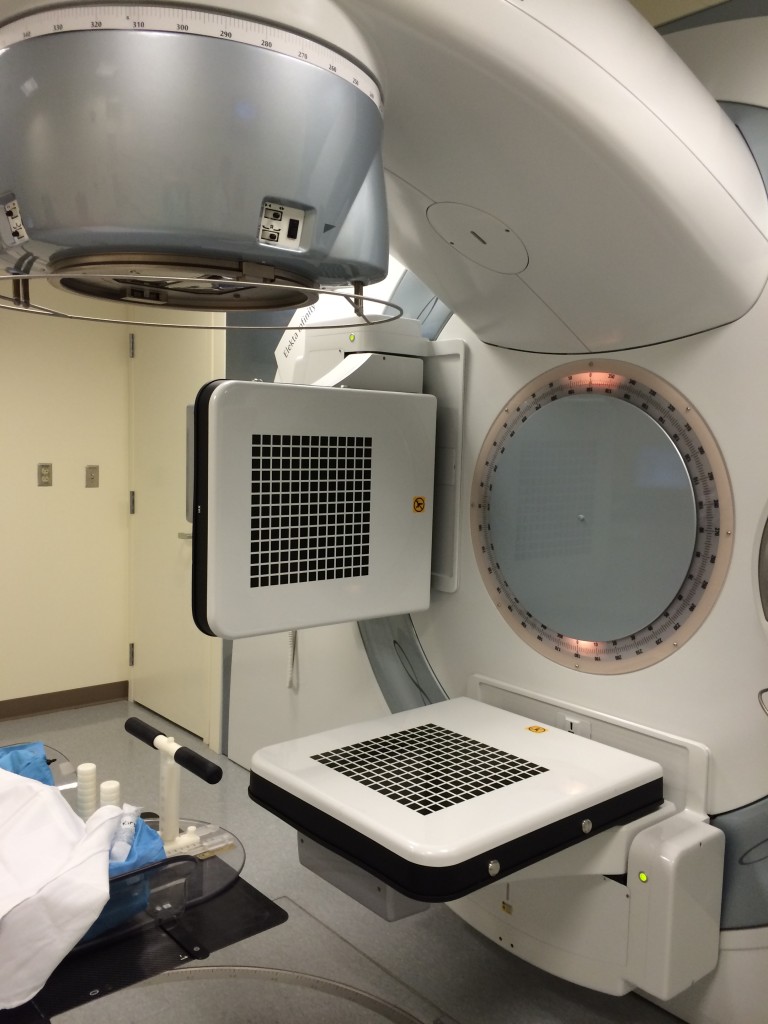

But no, nothing of the sort. The linear accelerator uses radio waves to speed up a stream of electrons to close to the speed of light; and magnets control the stream and focus it; and the beam hits a tungsten plate, and the plate spits out x-rays. On demand. A beam of x-rays, which then gets focused and further refined and shaped before reaching the patient.

There’s only radiation when the machine is actually being used. And only the exact amount that you need. And carefully focused, and precisely aimed — it’s a thing of beauty.

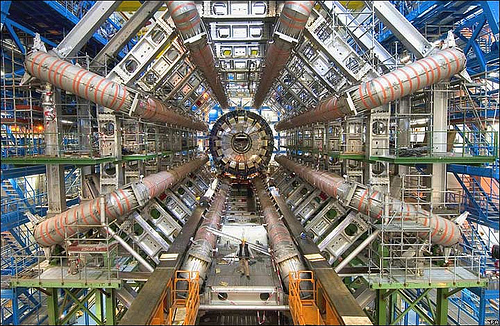

Plus: linear particle accelerator? That’s the same thing that feeds the initial particle stream into the Large Hadron Collider.

Okay, they’re using protons and we’re using electrons… but hey, same damn concept, right? How is this not cool?

I let the techs know that I was a science fiction writer, which helped explain to them my deep delight in this wonderful machine. They loved it too! They were proud of their machine, and proud of how it helped people — and they were resigned to the fact that most people were going to be afraid of it. And they did their best to calm the fears, and reassure their patients. But these ladies (and they were ladies — all the radiation techs were women), they knew what a fine technological accomplishment this machine was, and they were glad to be the ones using it to help save their patients lives.

And I was (and they told me this) the only patient to ever actually like the Elekta Infinity Linear Accelerator as much as they did.

Them: Do you want to see behind the scenes?

Me: Do I? YES.

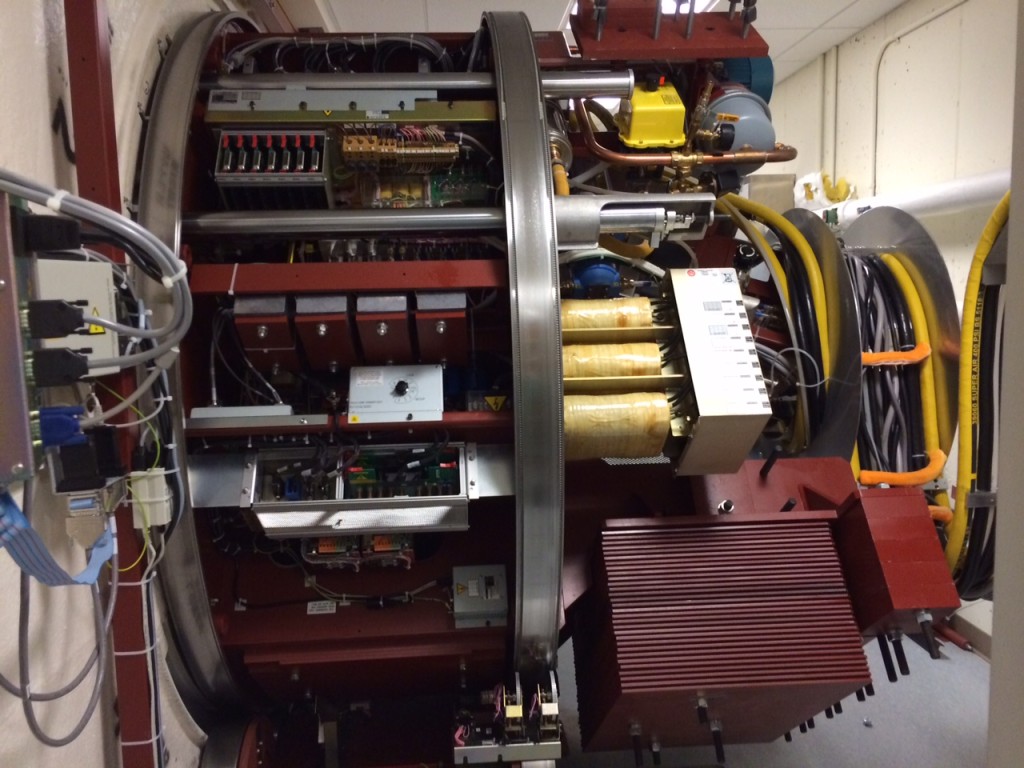

All the heavy lifting is done here.

Me: Well. Now it looks like a particle accelerator.

Them: (giving me the side-eye) And how many particle accelerators have you seen?

Me: Um. I took the tour of Fermilab, back when the Tevatron was operating. And of course I’ve seen any number of photographs of the Large Hadron Collider…

Them: (amused) Okay…

Yeah, it doesn’t look exactly like either one of those… but I feel I detect a sort of family resemblance.

Elekta’s big brother

So, what’s the point?

Cool trumps scary.

Eight weeks, five days a week, I’d sit in the waiting room with all the other patients scheduled before and after me. And when my name was called, I’d stroll on into the treatment room, cracking jokes with the techs, slide into position, let the techs micro-slide me into a more precise position; and the lights would dim, and the women would speak quietly to each other for a while, chanting numbers; and the laser aiming light would locate my position even more precisely… And the techs would step out of the room. And the gantry would hum and move about. And pause, and click a bit, and pause; doing its job, accelerating electrons up toward the speed of light…

I didn’t feel a thing.

It was over very quickly.

The machine never touched me.

But I had to resist the impulse to give it a little friendly pat on my way out…

Extra coolness because: lasers.

(Here’s a video by the company that makes the Elekta LINAC, that explains it all.)

(Added later: I’ve collected most of the posts about my cancer experience in one list here, if you’re interested and don’t feel like searching through the archives.)