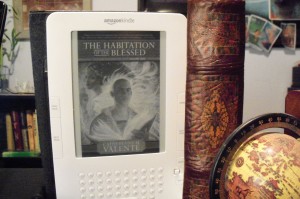

The Habitation of the Blessed: Dirge for Prester John, Vol. 1, by Catherynne M. Valente; and further discussion

The art of literature, vocal or written, is to adjust the language so that it embodies what it indicates. — A. N. Whitehead

I had originally hoped to have finished reading Catherynne M. Valente’s Habitation of the Blessed: a Dirge for Prester John, Volume 1 by today, so that I could write a review that addressed the whole of it, coming to some grand, deep conclusion — so that I could write, in fact, both intelligently and beautifully about this intelligent and beautiful book.

However, I find that Thursday has arrived, and I have not yet reached the end of the book — and that is, I believe, a very good thing in this case.

I could have rushed it, of course I could have — like most readers who love reading, I can read very quickly indeed.

But earlier, over in the comments, Sabine made this point : It’s one of those books, like Gormenghast, that forces me to read slowly and savor the prose. But I also have to stop reading after a chapter or so, just to cool down my brain.

If you try to read Habitation of the Blessed quickly, you’re making a big mistake.

A couple of times over the past few days, I did start to hurry, hoping to finish by today.   But each time some wiser part of myself stepped forward, grabbed me by the elbows, and shook me hard.  Stop, it said. Go back. Read it again. Look what you missed! I soon stopped trying to rush.

Because if you read a story very quickly, what you get from the story is this: the events.

That’s it. The stuff that happened. That’s all.

For some writers, that’s all they have; and for some stories, that’s enough.  So in reading them fast, you lose nothing — and even gain, perhaps, in the giddy glee of sheer speed.

But Valente has more for you.   She’ll give you what happened, but also the scent of it; and the cracking of blue light above; and the sorrow and joy of layered centuries; and delight, and the taste of especially good coffee; and the pain of remembered betrayal by someone who you didn’t know yet.

Life is not just events; it’s resonances and echoes, and knife-edged immediacy.

It takes more than plain prose to give these things to the reader.

I am a very bad historian, the monk Hiob says. But I am a very good miserable old man. I sit at the end of the world, close enough to see my shriveled old legs hang over the bony ridge of it. I came so far for gold and light and a story the size of the sky.

I am a Pentexoran, Hagia the Blemmyae says. I am a loyal and darling child of luck. I submit to it, like a dog. But it terrifies me, sometimes, how near we come, every moment, to living some other life beyond imagining.

I ate the sail one night and dreamed of honey, the starving traveler John says. The stars overhead hissed at me like cats.

I am not like you, Imtithal the Panoti says. I was made of other things than street-dust and spices, other things than cities can forge in their endless and wending hearts.

These are the four characters Valente gives us, to usher us into and through the Habitation of the Blessed: two men of the world we know; two women of the world of wild wonder.   They’ve led me halfway through the book thus far.

I’m rested now; my brain has cooled down a bit. I’m ready for more.

Let’s go on.